|

Friday,

October 12, 2001

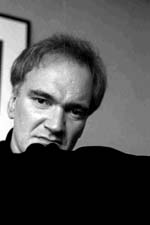

Talking

with Quentin Tarantino

Director expounds on ‘Iron Monkey’

release and the effects of the attack on movies

By Jack Mathews

Knight

Ridder

Normally, when a big-name director agrees to “present”

a foreign or obscure art-house movie in order to bring attention

to it in the mainstream press, the name is all you see.

But

in the case of Yuen Wo Ping’s “Iron Monkey,”

a 1990 Hong Kong action film that Miramax has retrieved from

the video racks for a major theatrical release, the presenter

— Quentin Tarantino — couldn’t be more enthusiastic

if he’d directed it himself.

“I

love Hong Kong kung fu movies, and Yuen Wo Ping is my favorite

director of them,” says Tarantino. “When Miramax

said Yuen couldn’t be here for the opening and asked

me to present it, I said, ‘Fantastic, I’ll be the

director in proxy.’”

In

fact, there’s an I-told-you-so element to the association

that Tarantino clearly relishes.

“I

told Miramax about Yuen six years ago,” Tarantino says.

“I said, ‘Get Jet Li, get Donnie Yen, put them in

a movie and get Yuen Wo Ping to direct it. They’ve never

done an American movie. Put them on contract.’ They said,

‘Yeah, yeah’ and that was that. Then came ‘The

Matrix’ and ‘Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon,’

and they wanted to be in the Hong Kong action movie business.’”

“Iron

Monkey” is the first of several archived Hong Kong action

films picked up for first-run release by Miramax in the United

States. If there’s a mainstream market for these films,

“Iron Monkey” is likely to find it. About a doctor

moonlighting as a robber who steals from the rich and corrupt

and gives to the poor, it’s essentially a Chinese version

of the Robin Hood legend.

“This

kicks it up on the action-adventure level, but it still has

the romance in there and it’s wrapped up in something

Westerners can identify with,” says Tarantino. “You

don’t have to know Chinese mythology or history to enjoy

the story, and the fights aren’t that violent. Kids can

enjoy it.”

While

the fight sequences resemble those fanciful duels Wo Ping

choreographed for “Crouching Tiger,” there are far

more of them. But it is still fighting as ballet, cartoonist,

illogical and masterfully inventive. Nobody seems to get hurt

badly enough to keep them down, and, given the timing of release,

that’s a good thing.

Still,

we can’t help wondering what Tarantino — who became

famous largely for his comic treatment of torture and mayhem

in “Reservoir Dogs” and “Pulp Fiction”

— thinks will be the impact of the Sept. 11 attacks on

movies.

“I

don’t really think things will change that much,”

Tarantino says. “The clichés may change. I think

that’s actually the history of cinema. The clichés

change, the tastes change, certain things go dormant for a

while, then they come back bigger than ever.”

Tarantino

says the kinds of films associated with him won’t be

affected, but movies like “Die Hard 2,” “where

you just blow up an airplane — boom! — that’s

going to change for a while.”

“I

have to admit when I watch a movie now and see a big skyscraper

or something blow

up, I think of those 6,000 people getting up that Tuesday

morning thinking they had their whole lives in front of them

and yet they didn’t even have the afternoon in front

of them.”

During

the week of the tragedy, Tarantino says, he played host to

a double feature for a few friends, showing them “Black

Sunday,” a 1977 film about a madman’s plot to terrorize

a Super Bowl crowd, and a compilation film he prepared using

action scenes from such mass-destruction films as “Die

Hard” and “Speed.”

“The

thing that jumped out at us, in light of the real tragedy,

is that (those movies) all seem very dated and quaint —

the whole concept of a brilliant criminal mastermind holding

a city ransom for millions of dollars. Dennis Hopper planting

bombs under the street (in “Speed”) just for the

money? That’s very quaint.”

Tarantino’s

latest project, “Kill Bill,” was put off until next

year when his star, Uma Thurman, became pregnant, and he says

he’s now happy not to have a movie in production.

“When

I run away with the circus, I want to run away with the circus,

and not have real life rearing its ugly head,” he says.

Given

Tarantino’s immediate success — his first two films

made him an international icon — his output has been

pretty thin. He’s acted in a bunch of movies, produced

a few, and put out a series of videos introducing his favorite

obscure films. But there’s been only one other feature,

1997’s “Jackie Brown.”

“People

think I’m not doing anything, but I’ve been working

my ass off writing,” he says. “I spent a year writing

a war movie I wanted to do, but it became like my great American

novel, and I had to set it aside for a while. Then I spent

another year writing ‘Kill Bill.’”

What

Tarantino says he’s guarding most against is becoming

a writer-director enchanted by big fees and a lifestyle that

puts you at their mercy.

“I

see so many writer-directors who become famous for their originality,

their voice, then get caught up in the (trappings of success).

They become professional Hollywood directors, they join the

union, get the big house and start living way beyond their

means. They have to keep making movies to keep up the lifestyle,

and to do that, they give up that thing that made them unique.

They can’t go back into the room and face the dragon

again.

“I

don’t want to make a movie for the wrong reasons. You

do that, and it’s hard to get back. If you fail on your

own, you can learn from the mistakes. But if you fail on somebody

else’s terms, you’re done.”

|